Brighton, Brisbane and Clontarf, Redcliffe Peninsula.

This is the full version of an article originally published in the book ‘Brisbane Art Deco: Stories of our Built Heritage’, reproduced here to mark the 80th anniversary of the opening of the Hornibrook Highway.

The Hornibrook Highway, connecting Brisbane and Redcliffe, opened on a blue-skied afternoon on 4 October 1935. “The hour is come!” proclaimed builder-contractor Manuel (M.R.) Hornibrook to a crowd of hundreds, as his bold ambition, years in pursuit, was finally rewarded. Today, a towering Art Deco portal, nestled in the rocky shores of Hays Inlet and Bramble Bay at Brighton on Brisbane’s northern outskirts, stands as a relic of the much lauded bridge, with the words ‘Hornibrook Highway’ affixed at its centre in blackened brass lettering. On the opposite bank at Clontarf, located at the southernmost tip of the Redcliffe peninsula, rests its identical twin. Until the bridge crossing was demolished in 2011, these portals majestically framed what became, on that opening day, the southern hemisphere’s longest viaduct over water, measuring 2.68 kilometres.

The man at the centre of this story, M.R. Hornibrook (later Sir), was one of the country’s leading building and civil engineering contractors, admired for his inexhaustible drive and exacting work standards. His family-run business, started in 1912, won public works contracts all over Queensland and further afield, inspiring associates to refer jocularly to it as the ‘Hornibrook Empire’. Building bridges sealed Hornibrook’s reputation, with more than 100 completed during his lifetime. Some of the more renowned projects that he and his construction team led include the William Jolly Bridge, Story Bridge (in partnership with Evans Deakin & Co.) and New Victoria Bridge in Brisbane, and the famed sail-like roof of the Sydney Opera House.

Constructing a highway in the early 1930s linking Brighton and Redcliffe was Hornibrook’s most ambitious project in his career to date. He first conceived of it years earlier, on moving to neighbouring Sandgate for a time. Hornibrook was struck by the isolation of Redcliffe residents who lacked convenient transport into Brisbane and the frustration of Brisbane holidaymakers longing for easier access to the popular seaside resort. The journey entailed a lengthy steamer or road trip, the latter on a circuitous route via Petrie that often flooded in wet weather. Brighton and Sandgate residents traversing the bay relied on local ferry services, such as the ‘Olivine’ and ‘Beryl’ motor launches managed by Humpybong Steamship Company, or a humble rowboat operated by local Redcliffe residents Charles and Martha Cutts. Passengers would signal for the rowboat by flashing a mirror to catch the sun’s reflection or making smoke on the beach.

The onset of the Great Depression propelled Hornibrook to make his vision a reality. Work evaporated as public funds dwindled so a project was needed to keep the business afloat and its construction force employed. A tenacious man who wielded influence, Hornibrook persuaded the Queensland Government to rubber-stamp his proposal for a privately constructed toll bridge, which required a special act of parliament to be passed, The Tolls on Privately Constructed Road Traffic Facilities Act of 1931.

The project was the first public–private partnership (or ‘PPP’) in Queensland and an early case study internationally of an approach to public policy that has grown exponentially since the 1980s. More specifically, the Hornibrook Highway exemplified what is now known as a BOT or ‘Build–Operate–Transfer’ project – it was designed, financed, operated and maintained by private enterprise under a 40-year franchise, at the end of which all rights and responsibilities transferred to the Queensland Government.

This novel approach to public works sparked heated debate on the parliamentary floor when the proposed Act was first mooted. The conservative Moore government, seeking efficiencies in public service provision, argued that the people should not bear the financial burden of capital works when private enterprise was willing to carry the cost. The Labor opposition, led by William Forgan Smith, countered that capital assets should remain in public hands and objected in principle to private tolls. In a more colourful moment, long-serving Member for Gregory, George Pollock, quipped, “…shortly a man will not be able to go outside his door without paying a tax for use of a footbridge. Why not put a tax on his garden gate or on a bridge across a culvert, and make this taxation palpably absurd?”. The bill passed parliament 25 votes to 21.

Construction of the Hornibrook Highway commenced on 8 June 1932, with Premier Arthur Moore turning the first sod on what he called an “epoch-making day”. Brighton’s Art Deco portal was the first component of the bridge completed in 1933, closely followed by its counterpart at Redcliffe. Designed as tollhouses, the concrete portals contained a small office and a strongroom with a night safe, and were connected by telephone wires placed inside the handrails of the bridge.

The portals’ architect was John Beebe, also a keen mathematician and astronomer, who hailed from Bendigo in Victoria and moved to Brisbane in 1916. He spent a decade in the Queensland Public Works Department before setting up private practice. It is likely that Hornibrook met Beebe through his association with the Hamilton Bowls Club, where both men occupied committee positions in the early 1930s. Beebe had designed the club’s new pavilion, which opened in 1931, and a year later he signed a contract with Hornibrook for the tollhouses.

Beebe’s choice of an Art Deco style is curious in the context of his body of work. While few records remain of his architectural footprint, his other known projects in Queensland, such as the Hamilton Bowls Club and Kirra Beach Pavilion, looked back to styles from the past. In any case, given the association of Art Deco with speed and progress, often symbolised by modern transport, it seems appropriate that the design for the Hornibrook Highway was classically of this style. The mass of symmetrically arranged vertical fins that adorn each pylon soars skywards, creating a stepped silhouette effect. This is balanced by an equally strong use of horizontal lines etched into the banded spandrel that connects the pylons and into the pylons’ rusticated bases. The tollhouse doors are framed by a stylised, low-relief geometric pattern. On approach to the portals are two smaller freestanding pylons which, in their tapered obelisk design, are reminiscent of the wave of ‘Egyptomania’ that influenced Art Deco styling. Viewed in their entirety, the portals exhibit a monumentality that suggests solidity and strength – important qualities for a bridge expecting high volumes of traffic.

The tollhouses quickly became a centre of attraction for weekend motorists intrigued by modern design. Newspapers of the day responded favourably, describing the portals as “spectacular” and “majestic”, revealing “the simplicity of modern architecture”. For locals, they were a source of community pride, transforming a mundane-sounding ‘viaduct’ into a stately ‘bridge’.

At the time the portals were completed, remaining construction slowed almost to a standstill as financial difficulties struck. Hornibrook Highway Ltd had been incorporated in March 1932 to raise private finance, in accordance with the government’s franchise conditions. By mid-1933, however, only £30,000 had been committed from mostly Brisbane investors, with construction projected to cost ten times that amount. The main stumbling block was the economic depression, the depth of which took Hornibrook by surprise. In true character, he later remarked that these circumstances “only strengthened our backs”, propelling the company to financially restructure. Hornibrook Highway Ltd was floated on the stock exchange in March 1934, attracting significant investment from Sydney and Melbourne. The National Bank of Australasia provided a £100,000 loan for the construction period, and this was repaid by a second loan from AMP Society when the franchise period commenced in 1935.

In a significant departure from the original terms of the public–private partnership, Hornibrook sought financial assistance from the Queensland government in 1933, in the form of a £100,000 guarantee on the loan. The Labor Party had assumed power by this time, and Premier Forgan Smith received the request favourably given the project’s contribution to employment. This was a marked turnaround from his time on the opposition benches when he strongly objected to the franchise. In another twist, the Country and Progressive National Party that originally advocated the project, vehemently opposed amendment of the Industries Assistance Act to allow the guarantee, arguing unsuccessfully during a protracted 14-hour parliamentary sitting that government had no part propping up speculative ventures, irrespective of social good.

With finance secured, construction proceeded quickly in the final 15 months. All materials used in the bridge, apart from reinforced steel, were manufactured in Queensland. Queensland Cement and Lime Co. (QCL) in Darra, for example, supplied concrete for the structure. It is notable that the Brighton portal was built from the first sample batch of concrete that QCL manufactured using coral from Mud Island in Moreton Bay. In 1931, Hornibrook himself had test drilled the coral deposits on QCL’s behalf, exposing what a University of Queensland geology professor described as a “virtually inexhaustible” resource for concrete manufacture. This marked the beginning of an industry lasting more than 60 years until coral dredging was prohibited in 1997 to protect Moreton Bay’s fragile reef environment.

One of the biggest challenges in the construction of the Hornibrook Highway was sourcing the 2.5 million super feet of timber needed for the corbels, girders and decking. Ever the entrepreneur, Hornibrook expanded the company’s interests into timber and sawmilling, securing large tracts of ironbark around Kilcoy, Jimna and Obi Obi Valley, and purchasing sawmills in Mt Mee and Conondale.

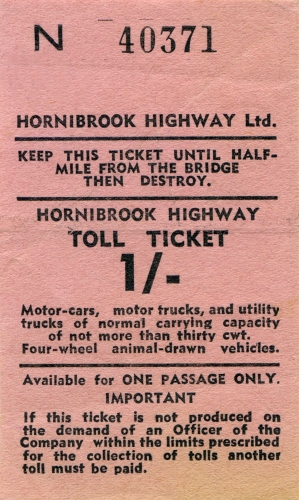

When the highway’s last plank was spiked in place on 7 September 1935 as darkness descended, a small, unofficial ceremony was held. A convoy of workers was first to drive across the bridge, followed closely by Hornibrook and the Redcliffe mayor. The official opening on a Friday afternoon almost a month later involved much more pomp and ceremony; the day was declared a public holiday in Sandgate and Redcliffe. The Governor of Queensland, Sir Leslie Wilson, cut a ribbon at the Brighton end with a gold boomerang, then proceeded across the viaduct to be welcomed by a Scottish pipe band at Redcliffe. Thousands of spectators turned out, arriving by a special train scheduled from Brisbane city or joining a long queue of cars waiting expectantly to cross the bridge. It was estimated that 3000 vehicles drove over before toll collection commenced at 6pm. The first motorist to purchase a ticket was Reinhold Dittberner of Boondall. His family later joked that he would have been disgruntled at having to pay the toll rather than appreciating the historical significance of the moment! A weekend of festivities followed, with a children’s picnic, ball and flower show among the celebrations in Redcliffe. The only glitch recorded on that first weekend was heavy congestion on Sandgate Road as 12,000 cars, a number far exceeding expectations, waited to pay their dues.

The toll road – Queensland’s first – proved popular from the outset, with motorists willingly parting with a shilling to save 15 kilometres on the journey between Brisbane and Redcliffe. The value for motorists only improved as the years passed since the one-shilling toll rate never changed, even with the introduction of decimal currency when it was converted to an equivalent 10 cents. The highway was publicised in tourist brochures and Brisbane papers as a “must see”, “a journey on wheels between sea and sky” and an “unequalled pleasure drive”. Concomitantly, business declined and eventually ceased for steamship companies that for decades had served the day-tripper market.

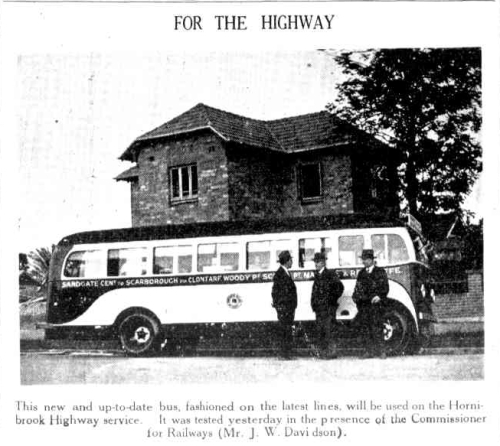

For the Hornibrook family enterprise, business only boomed in the wake of the project. The company was kept afloat during the depression years and around 500 men were employed directly or indirectly. Expanding business in yet another direction, the Hornibrook Bus Service was established in 1935, a green and yellow fleet conveying commuters from Sandgate Railway Station across the bridge to popular Redcliffe beaches. The highway experiment proved profitable as the company discharged its debt without ever calling on the government guarantee. While returns for investors fluctuated over the years, at the end of the franchise period the venture was declared a “golden goose”, not the “white elephant” that some predicted when subscriptions were first offered in 1932.

Hornibrook’s trailblazing into public–private partnerships also paved the way for similar enterprises to follow, most notably the Walter Taylor Bridge at Indooroopilly, approved under the same legislation. In a symbolic gesture, Hornibrook was the first to pay the toll when the bridge opened in 1936. The one win Hornibrook failed to engineer for private enterprise was an appeal to the High Court of Australia in 1939, in which he disputed sales tax charged on concrete piles used to construct the Hornibrook Highway. He argued that the piles were specially manufactured for the job and had no sale value within the meaning of taxation law, but the appeal was dismissed three judges to one.

On a larger scale, the Hornibrook Highway was the impetus for considerable development of the region. Population and property values both boomed in Redcliffe and new tourist infrastructure burgeoned. In a major advancement, Redcliffe was supplied with tap water from Brisbane for the first time through pipes built under the bridge. The area around Sandgate was also opened up to further development, including improved foreshore facilities, capitalising on the ever-increasing thoroughfare to Brisbane’s northern outposts.

Exactly 40 years after the franchise commenced, the Hornibrook Highway was handed back to the Main Roads Department on 4 October 1975, hundreds of residents once again turning out to mark the occasion. The final toll was paid at 6pm by Minister for Main Roads, Russ Hinze. Accompanying him was Ray Dittberner who, as a one-year-old, had been a passenger in the car belonging to his grandfather Reinhold when the very first toll was paid. Ray’s wife, Margaret, came prepared with an old shilling, which Hinze handed over.

The story of the Hornibrook Highway after the transfer was one of gradual decline. The 1970s were marked by major traffic delays as more than 20,000 cars crossed the single-lane bridge each day. In response, the Houghton Highway was opened just east of it in 1979, snatching the title of longest viaduct in the southern hemisphere by a mere 60 metres. Despite Hornibrook’s efforts to protect materials against the deleterious effects of sea air, close inspection revealed an unanticipated level of deterioration, prompting the bridge’s closure to vehicular traffic. Nonetheless, it gained a new life as a popular crossing for pedestrians and cyclists and as a favoured fishing spot for anglers. A third bridge, the Ted Smout Memorial Bridge, was opened in 2010 to help manage rising traffic volumes and offer an alternative pedestrian route to the Hornibrook.

A few days later, on 14 July 2010, the Hornibrook Highway was closed, deemed too expensive to restore and maintain. Thirty descendants of the Hornibrook family gathered at the Brighton end before the crossing was finally demolished, performing their own personal ceremony to declare its time passed. In the end, the decorative outlived the utilitarian, the concrete tollhouses still standing to be enjoyed by admirers of modern design, linking two neighbouring communities in a shared Art Deco heritage. The Queensland Heritage Register lists the portals as significant examples of this architectural style.

There are other, less conspicuous ways the Hornibrook Highway lingers on. Following its demolition, the bridge’s valuable ironbark decking and girders were sold to be recycled in building projects Australia-wide. Among the many examples of re-use are the restoration of a colonial-era suspension bridge in the Kangaroo Valley in New South Wales and the construction of the award-winning Garangula Gallery near Canberra, which houses Indigenous art. Designers of the gallery drew inspiration from the timber’s provenance, shaping it on the building’s façade to mirror the bends of the Pine River, which runs into the bay crossed by the Hornibrook Highway. Closer to the bridge’s home, timber remnants form part of a welcome sign at the end of the Houghton Highway as an acknowledgement of Hornibrook’s place in local history. In these respects, the legacy of the bridge continues, extending much further afield than Hornibrook himself would have imagined.

There is one final way the Hornibrook Highway lives on and that is as part of the community’s intangible heritage – in story, memory and identity. Popular poet and former Redcliffe resident, Rupert McCall, alludes to this symbiosis between the bridge as a physical site and as a site of enduring cultural meaning in his verse, The Boy on the Bridge Returns (1997):

The city doesn’t know me when the Hornibrook’s below me,

It’s a homely kind of journey that I’ve come to understand,

It’s an ocean breeze that cleanses something stressful from my lenses,

My wheels are heading north towards Peninsulated land.

The Bay lies like a mirror – non-reflective of its terror,

And the blue horizon meets it where the tower comes to view

Beneath a seagull-studded ceiling – it conveys a special feeling,

And I wonder in my wildest dreams if Oxley felt it too.

While the bridge itself is now gone, the Art Deco “tower” still “comes to view” on the journey from Brisbane to Redcliffe, standing as a tribute to local history, the Hornibrook legend and the flourishing of modernity in Queensland in the early twentieth century.

*Article reproduced with permission from Jubilee Studio. Originally published in: Wilson, K. (Ed.). (2015). Brisbane Art Deco: Stories of our Built Heritage. Brisbane, Australia: Jubilee Studio.

*Excerpt from The Boy on the Bridge Returns reproduced with the kind permission of Rupert McCall.

**If you enjoyed this article and would like to keep up-to-date with similar stories as they are published, please like the Queensland Deco Project Facebook page or subscribe to follow the blog.**

Image acknowledgements

Hornibrook Highway (front view), 2015. Queensland Deco Project.

Cars and pedestrians using the new bridge, 1935. Courtesy State Library of Queensland.

Manuel Richard Hornibrook, Master Builder and Managing Director of M. R. Hornibrook Ltd, Men of Queensland, 1929. Courtesy State Library of Queensland.

The ‘Olivine II’ ferry service taking passengers between Sandgate and Redcliffe, 1915. Courtesy Moreton Bay Regional Council. This image may not be reproduced without permission of Moreton Bay Regional Council.

Parliament House in Brisbane, Queensland, ca. 1937. Courtesy State Library of Queensland.

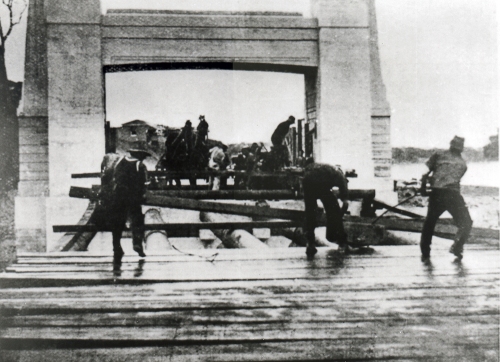

Premier Arthur Moore turning the first sod. Courtesy State Library of Queensland.

Architectural drawings of the portals, 1932. Courtesy Redcliffe Historical Society. This image may not be reproduced without permission of Redcliffe Historical Society.

Hornibrook Highway (side view), 2015. Queensland Deco Project.

Queensland Cement and Lime Company float on display in Brisbane. Courtesy State Library of Queensland.

Men laying the timber road, ca. 1930s. Courtesy Moreton Bay Regional Council. This image may not be reproduced without permission of Moreton Bay Regional Council.

Crowds at the south portal on opening day. Courtesy State Library of Queensland.

Toll ticket. Courtesy Dave Elsmore Collection. This image may not be reproduced without permission of Dave Elsmore.

‘For the Highway’, The Telegraph (Brisbane), 2 October 1935, p.18.

Entrance to the Hornibrook Highway from Sandgate, Brisbane, 1939. Courtesy State Library of Queensland.

The pedestrian Hornibrook Highway Bridge and adjacent Houghton Highway, with the Ted Smout Memorial Bridge under construction in background, 2009. Courtesy Ian Harding. This image may not be reproduced without permission of Ian Harding.

Hornibrook Highway (side view), 2015. Queensland Deco Project.

Select references

Extensive research was undertaken in the development of this article. The following represents a small selection of references used.

A Tale of Two Bridges: Hornibrook Highway, Houghton Highway. Brisbane, 1980.

Browne, Waveney. A Man of Achievement: Sir Manuel Hornibrook. P.E.P. Enterprises, Brisbane, 1997.

‘Hornibrook Highway Bridge.’ Queensland Heritage Register. Department of the Environment and Heritage Protection, 2013.

‘Hornibrook Highway Ltd (Incorporated Under the “Companies Act” 1863 to 1913).’ The Brisbane Courier. 31 March 1932, p. 9.

Westwood, John, Juanita Grayson and Redgum Television Productions (Producers). Beyond the Bridge: Hornibrook (DVD). Eight Mile Plains, Marcom Projects (Distributor), 2007.

Categories: Architecture

St James Theatre, Brisbane: A lost Art Deco cinema

St James Theatre, Brisbane: A lost Art Deco cinema  Look inside: The Home Builders Annual 1938

Look inside: The Home Builders Annual 1938  Mackay Civic Theatre: A lost Art Deco cinema

Mackay Civic Theatre: A lost Art Deco cinema  Was the Depression good for Queensland Art Deco?

Was the Depression good for Queensland Art Deco?

Love the description of the politics of it all. The more things change, the more they stay the same. Great to learn that that fabulous timber has been reused. Thanks for a great read.

LikeLike